If playing Doom had been a barrier to productivity in 1996, 1997 saw the release of Goldeneye 007 and Quake II as well as the Nintendo 64. It may have been as well that Momus had something to do, as 1997 does not seem to have started well. An article called “Sensibility” on his website detailed Momus’ life in March of that year and begins:

“What’s your culture and technology diet when your marriage has broken down and you’re living in visa limbo, out of a suitcase in a borrowed council flat in Lambeth?”.

It would seem that somewhere between summer of ’96 and this article the marriage between Shazna and Momus broke down, and led ultimately to an amicable divorce in 1999. There’s no detailed discussion of this, but we can read between the lines of songs on The Philosophy of Momus, Ping Pong and to some extent 20 Vodka Jellies to gather that perhaps their lifestyles, and goals in life, were not in the end compatible, and leave it at that. He continued to work on Shazna’s album released under the artist name Milky.

His list of current media and art is a time capsule for the year: Tracey Emin is exhibiting at the time (in more ways than one), he mentions the band Kreidler, who he would go on to work and perform with recording the song “Mnemorex“. He lists Squarepusher, Plug and Denim (whose album Novelty Rock I can also recommend). He hugely admires White Town (pseudonym of musician Jyoti Mishra), and correctly predicts that he will be a one-hit wonder and go on to be a success on the internet (currently he gets over half a million monthly streams on Spotify, and not just for “Your Woman“). He is not so happy with The Divine Comedy’s Short Album About Love, which is described as “glib”: the word “smarminess” is also used: perhaps, like many fans, he preferred it when Neil Hannon wasn’t famous and was a little secret. He was reading Derrida, Alan Warner and Adam Phillips (a book perhaps aptly named On Monogamy). Techwise he now has an Apple Newton – a PDA – to receive email. The Newton 130 also attempted via a stylus to recognise handwriting – no doubt badly – and was discontinued a month later. He is considering living in New York or Hong Kong – not Japan, yet, and has a JVC Digital Video Camera and a Roland PMA5, which was a touchpad based sequencer you could carry around, and thus, to some extent, compose on anywhere. It is also the year that the collaboration with Laila France – Orgonon – was released, and the Kahimi Karie album Larme De Crocodile, featuring his songs, as well as the collaboration How to Make Love (Vol 1) with Jacques (Jack / Anthony Reynolds – who went on tour supporting The Divine Comedy).

For the new, single, London based Momus, there was a return to a Momus of old. Living in London brought a vaudeville, music-hall edge and wit to the songs of Momus, whereas living in France had resulted in explorations of romance and love, and an Eastern influence had led to sci-fi, futurism and time travel. The concept behind what would become the new album was harsher, perhaps more bitter and twisted than the previous albums: more akin to the Ultraconformist, Tender Pervert or Don’t Stop the Night. In July of 1997 Hong Kong – a British Colony – was to return to Chinese rule after 100 years. The Ping Pong album press release imagines a club in Hong Kong post-July at which Momus – sponsored by the Chinese – sings songs satirising the British, creating new stereotypes of the evil occidentals. Momus himself is described as a traitor, following in the footsteps of Lord Haw Haw, Quisling and Ezra Pound, launching more and more absurdist visions of his own countrymen, his own flesh and blood.

The album also directly deals with the usual criticism of Momus by those who take him literally: the somewhat short sighted critics who accused him of “being” perverse, racist, paedophile etc. without, presumably, actually listening to the albums properly. At all times Momus is performative: taking on characters and describing their point of view. He puts on and takes off masks, costumes, avatars. While personal events in his life no doubt seed ideas for the songs, the more extreme events and characters are obviously not actually him. As we shall see when I look at criticism of this album, the misconceptions continued.

This idea of performing while wearing an “avatar” is taken literally here, and compared with the idea of taking out a game cartridge with one idea/song/character/meme and replacing it with another. This is related to an actual piece of technology that had impressed itself on Momus’ memory. In 1979 Milton Bradley (better known for board games) released a gaming system called Microvision – which actually featured replaceable cartridges containing game ROMS, innovative for the time, and the first example of a cartridge system of its type for a handheld, 10 years before the GameBoy. Not only could you replace the cartridge in the Microvision, but you also got for each game a sleeve which fitted over the system and revealed or blocked out some of the 12 available buttons and renamed them. Left/Right movement was generally controlled with a knob, a variable resistance dial. There were three main problems with the console: the small black and white LCD screen had a problem with the liquid crystal leaking, permanently damaging the screen, if you removed the back cover, the insides were dramatically vulnerable to electro-static discharge, and the buttons having covers put over them stretched the membrane beneath each plastic key to the extent they often broke. Games for the console included “BlockBuster” (Breakout), “Pinball”, “Connect Four”, but not actually “Ping Pong”. Many early games systems did of course have a version of “Pong”, the ubiquitous early computer game. How the album actually got the name “Ping Pong” is explained in the first song below, and the reason is of course ludicrous.

Ping Pong was released in October and followed in November by a European tour with Gilles Weinzaepflen – who performs as Toog. The tour was nicknamed EuroKong, and was followed in February 1998 with a tour of the United States called AmeriKong. These tours would be successful in promoting Momus to US students and to his fans in Europe, but unfortunately Momus would bring back more than memories from the European tour.

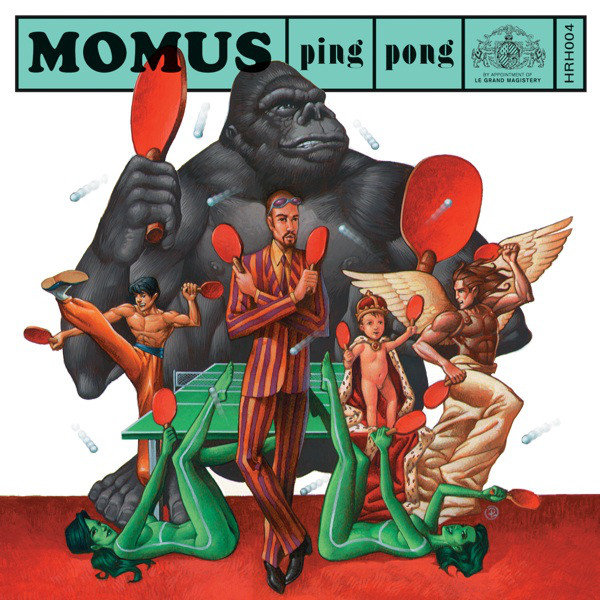

According to discogs.com, Ping Pong was released on Cherry Red in the UK with the most commonly used cover, and on Bungalow in Germany, and on Le Grand Magistery in the US, who released it just as they had also released 20 Vodka Jellies. My copy however says Satyricon Records/Setanta, which would be the Dutch release. The publisher at any rate was Rhythm King.

The UK cover is the preferred, displaying as it does the concept behind the album. The image of a unicorn was removed in the Greek version (perhaps for reasons of cultural resonance?) and the statement below the image displayed in large, curving letters instead.

The CD Cover shows the Microvision being used to play Ping Pong, which, as previously stated, wasn’t technically a title available on the console. MOMUS PING PONG is printed in all caps in a retrofuturistic font in the same yellow as the console’s front is displayed and with a registered trademark symbol cheekily after it. As I said earlier, the console’s case and front were detachable and could be replaced with covers appropriate for each cartridge. This seems to be on a black background with a single star, which could easily have been the type of image you would have got in an advert for the device. Under the word Pong is a prog-rock cover image of a Unicorn standing in front of mountains and on what looks like marble. How this fantasy image fits into the general theme is not clear, but it may represent fantasy, and the imagination. Under this the advertising blurb for the console is printed in yellow sans-serif: “A new concept in electronic song systems – a hand held console with interchangeable characters. A wide variety of avatars available, see back.” At the bottom right of the cover in very small writing we get “9 Volt imagination required. Not included”: a dig at any critics who do not grasp the concept being presented. “You Lose Turkey” is written on the left hand side next to the spine, with an illegible Score, Top Speed and Time. The Microvision was certainly not easy to play, if you want to see it in action here is retro-game enthusiast Ashens having a go.

The back cover lists the 16 tracks down the left and under this is an image of someone removing the Microvision’s cover, possibly to play Pinball. This is over a simply drawn rainbow with five colours and further instructions: “Easy-to-insert, interchangeable game characters snap into the console. To change persona, simply remove one character and drop in another”. There is also a large image of the actual cartridge, this one mocked up to say “Professor Shaftenberg”, who we will meet later. He is described on the cartridge as a “Funkrageous Cabaret Gouster”: David Bowie recorded but did not release an album called The Gouster, a funk album which eventually “became” Young Americans. It is available on the “Who Can I Be Now?” box-set. “Gouster” according to producer Tony Visconti refers to “a type of dress code worn by African American teens in the ‘60’s, in Chicago… in the context of the album its meaning was attitude, an attitude of pride and hipness.” For the Professor, the funkiness is the reason for its use.

The CD inlay tray has Momus’ face in close-up, but Photoshop or similar used to make it look like a pencilled drawing in colour. The CD itself has Momus and Ping Pong written above and below the centre in the same yellow font as the cover. There is an image of someone seeming to draw on a screen using a stylus and with an old tablet controller: I am not sure what this is but it may be the Magnavox Plato. The disk contains regular info related to publishing by Rhythm King and lists Bungalow and Satyricon. The background colours of the disc are a deeply orangey yellow and a deeply orangey red. Sorry if that is too technical.

The CD inlay booklet has on its back the track listing as on the back cover of the CD and another mocked up cartridge, this time for “Mister Tamagotchi” : “Arrogant Digital Pet”. The rainbow is there again and under the console it says “Futuristic Vaudevillians, Thanks for pressing play! Please put on your avatar masks, Our game is under way…”. These are taken from the lyrics of the first song, and demonstrate again the “avatar” concept of the album and also in the line “Futuristic Vaudevillians” tells us that we can expect the kind of music we encountered on Ultraconformist: retro-futuristic music hall, anachronistic in style and content. There is also a hint in that phrase of the “Analog Baroque” concept which will become fully apparent on the next album.

The credits on the back here tell us all songs were written by Momus (no mention of Beck), and the sleeve designed by Momus. It was recorded at “The Meat Market” in London, which I think might just be his flat. Photography is by Riho Aihara at The Crow Bar, Exmouth Market. Thanks are given to Shazna, people at several record companies, Kahimi Karie, Anthony Reynolds, Bidisha (teenage author of the novel Seahorses), the artist Georgina Starr, and others including Mike Alway, the band Pizzicato 5 and “the Setantans”.

The inside back cover shows what could be an image of Momus’ flat but is certainly a bottle of Absinthe. The booklet has the lyrics in white text on gradient backgrounds in various soft colours. I don’t find it easy to read anymore without glasses, or possibly Absinthe. Each song has a small, thematically appropriate image accompanying it. There are a lot of lyrics. I am especially not looking forward to explaining “2PM“.

Ping Pong With Hong Kong King Kong (A Sing Song)

In his song by song description, Momus says he was asked to write a theme song for a potential film version of Pingu, to be made in Japan for their market. Pingu is a claymation animation – a Anglo-Swiss co-production, made from 1990 to 2006, and with a current Japanese production from 2017. It concerns a penguin and his family, and their misadventures. Pingu is well known for his gibberish speak known as “Penguinese”. According to Momus, the lyrics of his theme song/jingle were “Pingu the penguin, riding upon your sleigh, tell me what adventures you are going to have today”. If this is true, and like I said, it sounds ludicrous, I would ask how Pingu is expected to know what adventures he is going to have today, and, furthermore, how you expect him to tell you when, famously, he doesn’t speak any recognisable language. At any rate, you can now see how the happy coincidence of the word “Pingu” being nearly identical to “Ping” as aligned with “Pong”, a computer game. Also rhyming with Hong Kong, the transfer of which is a theme behind the album as discussed, and King Kong, just rhymes and is fun, and is a wild and crazy guy.

The song begins with a rush of 8-bit techno, the jingle that would accompany Pingu’s song played on what sounds like a Casio, with a layered keyboard sound including some kind of whirring wind noise in the background and a tinny beat. The jingle repeats with an organ part subtly in the background and Momus’ voice which is either multi-tracked or repeated with a slight delay, to sound fuller. The lyrics fully place this album in Ultraconformist territory, a song to welcome us to the show, a Burlesque or Music Hall Cabaret is promised, and the word “vaudevillians” promises humour. The lyrics on his site and on the album say “vaudevillain”: is he saying something about his fans or the characters, or is it an alternate spelling? Anyway, “don’t worry”, this album is telling the long established Momus fan, “this time it won’t be dark and gloomy”. The “futurism” is encapsulated in the thanks for “pressing play”: this is a CD, cassette or download, not vinyl.

“Ping pong the album

Comedy cabaret

Futuristic vaudevillains

Thanks for pressing play!

Futuristic vaudevillains

Thanks for pressing play!”

The song then has Momus chanting into the mic:

“PING PONG! HONG KONG! KING KONG! SING SONG!”

Before restating the main idea of the album: we are putting on characters, so is the person who is listening to the album: we are all actors.

“Please put on your avatar mask

Our game is underway!

Please put on your avatar mask

Our game is underway!”

The music stops abruptly after this, and we switch to a live recording after a moment of silence. A loop of a sound effect, something like a cello string being scraped, is playing. Momus is speaking to the audience:

“I don’t know what the technical word for it is, if misanthropy is not liking men, and misogyny is not liking women, what is the word for not liking babies, I don’t know..” There is some laughter, and someone shouts back “Normal!”, which receives more laughter, and someone (else?) shouts “Nick, you’re a legend!”, in a somewhat accented voice, very different to Nick’s. The track then switches to the second song.

Now, misanthropy is a dislike of mankind, rather than man. A dislike of men specifically is called misandry. A dislike of children would presumably be called paedophobia. But that just sounds weird.

The person who shouts “Nick, you’re a legend” (Not clear if he also shouts “Normal”) is John Quin, clearly a long term fan who went on to write a very complimentary review of Momus’ book “The Book of Scotlands” for Art Review magazine in 2009.

Edit: From Mr. Quin: “The guy who shouts ‘normal’ is Prof Martin Turner, Oxford neurologist, expert in MND.”

His Majesty the Baby

Now single, or now at least able to state his true feelings on the matter of babies, perhaps, Momus is no longer in any way broody, because he bloody hates the things. Who can blame him?

Jonathan Swift (Satirist and author of Gulliver’s Travels) wrote “A Modest Proposal For preventing the Children of Poor People From being a Burthen to Their Parents or Country, and For making them Beneficial to the Publick” in 1729: a satirical suggestion that the Irish, in the grip of famine, should consume their children because: “A young healthy child well nursed, is, at a year old, a most delicious nourishing and wholesome food, whether stewed, roasted, baked, or boiled; and I make no doubt that it will equally serve in a fricasee or a ragout”.

China, with its 1-child policy, could also be said to encourage infanticide. Hong Kong was returning to China. The execution of unwanted children was a reasonable topic for discussion, and to this performative Momus, ALL children are unwanted children, by himself at least.

For the lyrics of this piece, Momus made an appeal to authority, to Sigmund Freud, who believed that every baby considers himself a King. This would be a reasonable assumption to make if every single thing was done for you and every cry you made was instantly answered. Momus sees the “baby” as the enemy of feminism: the baby turns women into “obsequious, fawning imbeciles”, against their own desires, but more importantly, against their desire for Momus. He complains that having become a well-read, intellectual powerhouse, “…you find that women are biologically programmed to respond to gurgling, smelly, egocentric goons. No, not Oasis fans. Babies. Come the revolution, off with their heads!” This is not a reaction against women, at all, but against their rebellious biological imperative, he is on their side and wants to free them, and many women probably agree.

Freud himself would probably also want to talk to Nick about being the eldest of three children, and how he felt when his sister was born and took some of his parents’ attention from him. Actually, probably took all of it, for a while. Freud would read this answer given to a question in an interview with Chickfactor in 1998:

“I was at boarding school, not particularly happy. my parents had just come back from greece. you being my therapist, the two big shocks of my life were: I thought I was incredibly special being the first born in my family, then my brother and sister came along and I realized I was just another person, which is an essential realization for anybody to make. then being sent away to boarding school and realizing the world is full of bigger stronger guys who want to dominate you and who are less smart than you but ultimately can have their way because of more muscle power.”

Freud would read this comment on Momus’ own site about his sister Emma and his parents’ divorce, which we have mentioned before:

“I think I was probably the narstiest (sic) person in my family, but it wasn’t major stuff. I nicknamed my sister “Little White Pig” just in case my mother’s affectionate name for her, “Little White Pet”, went to her head. It was for her own good, you understand. Apart from that, everyone in my family was gentle and supportive and civilized to each other. We grew up in an atmosphere of mutual support and kindness which only broke down into mildly sarcastic recrimination when my parents divorced.”

Emma has opened a café called “The Little White Pig” in Edinburgh, so there are probably no hard feelings there. Nevertheless, Freud would probably shut his casebook with a satisfied grunt, content that the existence of this song was always inevitable.

After the live clip we are back in the “Meat Market”, and the song opens with gusto, a music hall stomp with double bass, staccato guitar chords and a tinkling xylophone, a near-stereotypical French accordion sound and Momus breathily intoning:

“Crooked smiles, mongol eyes and a toothless grin”

A jovial start stop to the now carnival-esque tone with a whistle playing us into the verse:

It is a perfect volley of hatred to the “king” with a parade of jealous insights:

“I hate his majesty the baby

His bowels and bladder uncontrolled

Sitting astride a throne of nappies

As though his shit were made of gold

As though a cherub on a fountain

He suckles breasts as big as mountains

Then pisses freely on the women

Who so lovingly surround him”

A stronger bass and piano accompaniment come in now to emphasise the switch from observing the “king”‘s perks to more violently verbally assaulting him: “bald and dribbling little git” is especially good because it is the last sort of language you expect from the normally eloquent and well-versed Momus:

“I hate his majesty the baby

The bald and dribbling little git

The polymorphous little pervert

In every orifice a fluid

Born in a filthy burst of semen

Some tosser planted in a woman

The spitting image of a tosspot

Let us assassinate the despot!”

The “chorus” introduces a theremin sound (or an actual theremin?). It follows what was discussed above: Momus sees himself as a feminist, freeing women from the expectations of society. He wants to sacrifice the “tyrant” by tearing it limb from limb. Compare if you like to the climax of the film Mother! directed by Darren Aronofsky. Freud would certainly ear up his pricks to the mention of Momus’ brother. I think calling him an “imbecile” is more gentle support for his own good.

“And if you cooing mothers should come cooing around me

Will you be ready for the struggle, the struggle to be free

From the instincts of your gender, from your social role as mothers

When I execute your tyrant will you claim me as your saviour

Or simply tear a traitor limb from limb

Fuck my imbecile brother, then begin again?”

There is an instrumental break with a keyboard playing a melody based on the verse and leading us into the next: the theremin comes to the front now, comically playing up to everyone’s expectations of a theremin from a 1950s sci-fi movie.

Momus delivery of this verse is excellent, and very comic. He is appropriately calm until the ladies demand what the baby has done to him, then “This bastard’s shitting on my shirt” is delivered with genuine venom as if from experience, with the sudden shift in tone raising a laugh , and his demand for an execution is heartfelt.

“I hate his majesty the baby

In my pathetic jealousy

I hear the voices of the ladies

Demanding what he’s done to me?

This bastard’s shitting on my shirt

I’m deep in excrement and dirt

I demand a revolution!

I demand an execution!”

He goes on to explain why he is so angry: he has tried so hard to be elegant, witty, seductive, but it is all for nothing when the ladies meet a baby: the end of this verse brings in further bass sounds and the theremin becomes more menacing, along with the backing. When he rasps “I hate you, imbecilic women”, he sounds incredibly genuine, misogynistic and consumed by rage.

“I’m well versed in fencing, playing the lute, and rhetoric

I am toilet trained and elegant, an effervescent wit

But the girls prefer the company of a balding little pisser

It is mothers who make men misogynists

They could have kissed me, they chose to kiss

A stupid, stinky little pool of piss”

So the next verse as I suggested above is the acme of his anger, as he vents his major threat: I hope your child grows up as twisted as I am. He mirrors American comedian Bill Hicks’ sarcastic routine about “the miracle of life” (Hicks talked about those miracles happening to white trailer trash every day, to mock the pseudo religious worship of “birth”.) Momus points out that it is not that difficult to make a life, so let us remove this “king”, the belief that babies are for some reason important, or more to the point, that they are more important than him.

While we are here, the NME review of this album included the observation “Nick Currie is a man who likes to wash the soiled laundry of his mind in public. Why else songs with subjects as tasteful and diverse as tossing off babies, sex crimes, bondage, Japanese schoolgirls and barely-suppressed misogyny?”. Needless to say, this review completely misunderstood the whole album project: the characters singing the songs are not Nick Currie. This is clear from the cover, the back cover and the first song. He has taken “I tossed him off one day at lunchbreak” to mean that he – Nick – took a baby behind the bike sheds and manually relieved it, which is both impossible and … obviously not what the lyric means. It means he completed the task of creating a baby with no thought or interest – he “tossed it off”, like a poorly written review due in by four o’clock. It is almost as if the writer deliberately misinterpreted the lyric in order to attack Momus following some agenda. The “barely-suppressed misogyny” is not barely-suppressed here at all, Momus is openly misogynistic in this song. As a character. As Nick Currie, he believes motherhood can be a barrier to female liberation. Which is the opposite to being misogynistic. We will come onto the Japanese schoolgirls later. So to speak.

“I hate you, imbecilic women

Who gawp around His Majesty

Don’t you know he’ll grow up, God willing

A twisted little shit like me?

I tossed him off one day at lunchbreak

One human life is not that difficult to make

Let us assassinate this despot!

His Imperial Majesty the tosspot”

The music slows down momentarily, the theremin and sound effects buzzing in the background as Momus declares the death sentence, couched in the language of the French revolution:

“O King, now you have reached the Age of Reason

The facts of life are laced with treason

There is going to be a sudden palace coup

And my new mistress, Madame Guillotine, will soon be nursing you…”

The music returns to the melody of the verse and Momus speaks the final lines over it.

The xylophone sound accompanies this directly. He whispers the conspiratorial line “let’s do him in!”, bringing us into his madness. A keyboard line then spirals upwards for the final few lines towards a climactic declaration of the climax he promises you: Momus will show you LIFE, again whispered, and its imperial majesty. Which I have a horrible feeling may be his nickname for his todger. The song finishes on a flourish, very much a vaudeville song and very funny.

“Crooked smiles from toothless gums

A grating voice and a stinky bum

Mongol eyes and a toothless grin

The king is naked — let’s do him in!

It’s time to rise up free from tyranny

Wouldn’t you rather be with me?

I’ll show you, ladies, LIFE

And its imperial majesty”

So the old joke about a man who finds a genie and wishes to become irresistible to women, and is then made a baby, is made violently funny. One final thing we should address, am I bothered by the word “Mongol”? As I mentioned before, my daughter has Down syndrome, is this word offensive? Not to me in this case, because I know why he is using it. It fits syntactically. And he is using it as an insult, so he must understand that it is offensive, and that is exactly why he is using it to insult his target. I doubt he would use it as an insult against a Down syndrome child, because why would he? Whatever biases Momus has, I doubt he has a problem with the disabled. We may examine some of his discriminatory behaviour later.

My Pervert Doppelganger

Edinburgh was the inspiration for Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr Jeckyll and Mr Hyde. Momus describes it as the civilised harmony of the Georgian New Town contrasting with the bawdy and debauched Old Town, just as Dr Jeckyll, as a product of civilised society, contrasts with Mr Hyde, the primal form of himself.

This song similarly describes the narrative in a battle between Momus, the civilised, urbane, eloquent, creative thinker and Momus, the dark, perverse, murderous mirror image of humanity.

The late 80s and early 90s in the United Kingdom had seen a crisis in beef production: the disease Bovine Spongiform Encepalopathy had been in offal fed to cattle, resulting in the cattle carrying BSE which transferred to humans as Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, prions – proteins – attaching themselves to brain and neural tissue and destroying it. The panic ensuing this discovery of the bleeding obvious: that forcing animals to be cannibals leads to serious illness: led to exports of British Beef being temporarily reduced or banned and the Minister John Gummer force-feeding his daughter a burger in front of the national press to prove British beef was “safe”.

Rather of relevance to 2020, the song is about Smithfield market, which Momus described at the time as “the quaint wrought-iron building at the heart of London’s rank and putrid meat dissemination network”.

The song begins with a tango: bass, marimba, percussion and a squealing synth noise, like radio feedback. The tango is a rough pastiche of “Tea for Two”, and like that song introduces a dance for two combatants. A flurry of percussive cha-cha music leads into the verse. Calmly spoken over the dancehall backing which contrasts the traditional sounding rhythm and percussion against the electronic squeals of a perverse future. It is interesting that the pervert comes from “across the sea”: much as Momus himself has a different life in Japan.

“I’ve got a pervert doppelganger

He came from over the sea

He hangs around doing sexual crimes

And the blame is getting pinned on me

The blame is getting pinned on me”

There’s a short instrumental break/bridge into the next verse:

We already know that Momus is a fan of Squarepusher and Green Tea.

“Whenever that pervert shows his face

My friends all think he’s me

They give him records by Squarepusher

And a box of Japanese tea

A box of Japanese green tea”

The next verse continues with the more sinister sounds increasing a little in intensity. The electronics peak on mention of “the Smithfields Ripper”, giving form to the horror of those words.

“He’s taken a flat in Smithfields now

Where refrigerated lorries unload dead cows

They call him the Smithfields Ripper now

And the rap is getting pinned on me

The rap is getting pinned on me”

Music hall style melodies are in the background of the song throughout, and for the next verse the song moves up a key as the doppelganger’s plan moves up a notch: he pretends to be Momus to make a date with his girlfriend. Momus adopts a different gruff, low voice when being the doppelganger. Does the girlfriend know he is a different person? Does she care?

“And now my pervert doppelganger

Has got my girlfriend’s phone-number

I gave her a warning, but yesterday morning

She cancelled her date with me

‘And made it a date with me!'”

This verse is followed by an instrumental break played on chiming bells, the sound of which contrasts with the setting, the other instruments and the dark nature of the lyric. The break ends with a descending, staccato series of tones on the synth leading back to the lower key. Momus, knowing his girlfriend has made a date with himself, confronts him:

“I went to the flat of my doppelganger

I’d copied my girlfriend’s key

I waited in a cupboard till they both came round

Then jumped out very suddenly

Jumped out very suddenly”

This is followed by more of that descending synth noise, and you can clearly hear the piano playing very familiar music hall chords in the back, reminiscent of the piano in “Forests” on Ultraconformist. The song lifts a key again: we don’t know what happened after Momus jumped out, but someone has been overpowered and taken away.

“And now we get along like a house on fire

The police took away my doppelganger

He’s a high security prisoner now

Being held under lock and key

And everybody thinks, thinks he’s me”

The coda talks about making love on top of piles of “slithering meat”, playing with fears related to BSE at the time, but still highly relevant now. Every line is sung to the same little melodic riff, which repeats as he chants “Can the man in the mirror be me?” finally resolving to the line “can it be… my pervert doppelganger?” Momus could be having a little dig at Michael Jackson here, and his song “Man in the Mirror“, not that he is accusing him of anything, of course.

The electronics return along with a piping recorder sound and the song ends with percussion clattering and the electronics winding down.

“And when the lorries unload their cows

Their hogs, their heifers and sows

In piles of slithering meat

I give my girl a treat

With unstoppable energy

Can the man in the mirror be me

Can the man in the mirror be me

Can the man in the mirror be me

Or can it be

My pervert doppelganger”.

The final joke, of course, is that we don’t know who is the “real” Momus and who is the pervert, or which one is under lock and key at the end. One is a genius, the other’s insane… but as with Pinky and the Brain, we are never told which is which. This is a delightful, funny song playing with Momus’ image of himself, and the “perverse” image others have of him, and toying with stereotypes of music hall, cabaret and vaudeville. The song uses electronic effects and synthesizers to approach the Victorian style from a modern angle, perhaps pointing the way towards the collision of eras that would become Analog Baroque.

I Want You but I Don’t Need You

This is one of Momus’ best known songs, on YouTube at least, thanks to Amanda Palmer’s live cover, videoed at the Metro in Chicago in 2008, which has over a million views. “Good Morning World“‘s official video by Kahimi Karie has 88k views by comparison, and “Hairstyle of the Devil” 150k.

It’s a song about psychologist Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: at the lowest level, we NEED food, water, shelter, heat, if those needs are requited, we move up the pyramid toward more complex “needs”: companionship, society etc. and at the apex of the pyramid: self-actualisation, the ability and opportunity to be creative.

The song Momus has written argues, again from a feminist perspective, that in the modern world we have everything we NEED and therefore life revolves more around the things we WANT. We have all the food, water, toilet roll we require (er.. normally), and therefore we are more concerned with the things we WANT, such as games consoles, sex toys, and subscriptions to Netflix. It is evidence of the progress of society that NEEDS become less important as time goes on, and WANTS become the target of our desire. Momus argues that women are still trapped in an economy of NEED because “they still need men to support them while they’re needed by the babies they bear” (and which he can’t bear). He expresses the hope that this will have changed when women earn as much as men, around 2010. Absolutely, racing to their equitably recompensed work on their Back to the Future hoverboards. The song argues that to be “wanted” is a superior thing to being “needed”. I NEED a plumber to stick his hand in my u-bend and get my fluids moving, but he shouldn’t feel as special as the man I WANT over to er.. stick his hand in my u-bend and get my fluids moving. The implication is that if the need was not there, most relationships would not exist, because there is no “want” to back it up.

The Q magazine review of Ping Pong (lukewarm and uncomprehending) says that the music for this song is as sleazy as Pigalle (a red light district in Paris, on the edge of the 18th arrondissement and the area mentioned in “The Charm of Innocence“), which is a little misleading. It begins with acoustic guitar, and a tinkling organ sound something like a fairground ride, in a waltz-time. The keyboard organ sound plays descending thirds, with a switch to a minor key after the first line, then back again to major: the minor tells us we are not needed.

“I like you, and I’d like you to like me to like you

But I don’t need you

Don’t need you to want me to like you”

The keyboard organ stops here, and the acoustic guitar becomes more prominent:

“Because if you didn’t like me

I would still like you, you see

La la la”

The keyboard returns now, but playing chords rather than individual notes, slightly beefing up the sound. The lyrics switch from verb one “like” to verb two “lick” which is funny, the slight assonance of the two making it an unexpected twist the first time you hear it.

This whole song is full of the sort of word play we expect from Momus: later on, “need me to meed you to need me” and “I’d like you to leave me to leave you” are reminiscent of the verbal tricks we heard on Tender Pervert such as “I’m jealous of the man the man you broke your heart of broke the heart of” from “A Complete History of Sexual Jealousy“. As so often with Momus, you have to listen carefully to unpick what is being said.

“I lick you, I like you to like me to lick you

But I don’t need you

Don’t need you to like me to lick you”

Unlike on the first verse, the keyboard organ stays for the second half this time, and the slightly sinister declaration of “personal gain” highlights the selfish nature of the narrator:

“If your pleasure turned into pain

I would still lick for my personal gain

La la la”

For the next verse a bassline kicks in and the keyboard starts playing higher and longer, sustained notes, two contrasting sounds which themselves contrast with the earthy nature of the third verb we are confronted with.

Part of me wishes it wasn’t “fuck”. Partly because it limits the radio play the song can receive, or could have received, without being edited and thus negating the point of having it in there. But mainly because the song is about the difference between “want” and “need”, and the difference between the sexes in this respect. By adding in the verb “fuck” you necessarily have to have a subject and an object: someone is fucking and someone is being fucked, and this implies a power dynamic, inevitably. Drawing our attention to this power dynamic removes our attention from the dynamic which was under discussion: “want” versus “need”. That’s just an opinion of course, you may violently disagree. It just seems that the “fuck” in this song is actually just there for the sake of it, and I don’t usually think that of Momus’ content. I’m not censorious in any way, by the way, that should be obvious from these reviews, but I do believe in words requiring a value to be placed on them. Apart from anything else, the rest of the song suggests an emotional attachment (whether want or need) in the relationship, but this verse denies it.

“I fuck you, and I love you to love me to fuck you

But I don’t fucking need you

Don’t need you to need me to fuck you

If you need me to need you to fuck

That fucks everything up

La la la”

Now there is a lovely key change, and a mandolin sound appears, just beautifully tinkling in the background:

“I want you, and I want you to want me to want you

But I don’t need you

Don’t need you to need me to need you”

The melodic lift now on “just me” is an aching void of loneliness: He knows it is going to be “leave me”, one way or the other.

“That’s just me so take me or leave me

But please don’t need me

Don’t need me to need you to need me”

The melody picks up again, the next lines ironically cheerful – we are headed for the grave, so love me while you can – before descending again for the final line:

“Cos we’re here one minute, the next we’re dead

So love me and leave me

But try not to need me

Enough said

I want you, but I don’t need you”.

There is a guitar solo here, a twanging acoustic guitar following the verse melody, the mandolin sound playing behind, then “la la” vocals leading into the next verse: the instrumentation remains as for the previous verse, with the keyboard playing chords, the mandolin no longer playing. We go to the final, most important verb now: “Love”:

“I love you, and I love how you love how I love you

But I don’t need you

Don’t need you to love me to love you

If your love changed into hate

Would my love have been a mistake?

La la la”

The decision made, the narrator knows his partner needs him to love her, and that is the exact thing he does not want. The vocal is louder here, and the mandolin returns as the emphatic decision is made on the word “leave”. A double tracked backing vocal follows Momus here, the mandolin leaves after the second line.

“So I’m gonna leave you, and I’d like you to leave me to leave you

But lover believe me, it isn’t because I don’t need you (you know I don’t need you)

All I wanted was to be wanted

But you’re drowning me deep in your need to be needed

La la la”

The song moves straight back into the verse melody. The music is very French, very music-hall, very 60s and with the mandolin added somewhat reminiscent of “The Third Man”, or a spy-film theme from the era. Again the melody lifts on the line “That’s just me”, then falls down as the line “Don’t need me to need you to need me” puts the final nail in the relationship, with the mandolin sound on the keyboard hitting the emotional beats on its high notes. At the end of the verse the guitar strums loudly and finishes the song quite abruptly.

“I want you, and I want you to want me to want you

But I don’t need you

Don’t need you to need me to need you

That’s just me

So take me or leave me

But please don’t need me

Don’t need me to need you to need me

Cos we’re here one minute, the next we’re dead

So love me and leave me

But try not to need me

Enough said

I want you, but I don’t need you.”

This is a quite brilliant song, my slight semantic misgiving aside, it says more in its four and a half minutes about the differences between men and women in relationships than a truckload of chart pop does. It’s intelligent, analytical, emotional and philosophical. It should have been a number one hit in every country. But there you go.

Professor Shaftenberg

The CD ROM which Momus made – This Must Stop! – featured a lunatic called Dr Heinboldt Muchenwald Murzenschlifferbach, a nonsense name, who was a psychoanalyst who had discovered, so he claimed, six new sexual neuroses. Prof Shaftenberg is an extension of him, a German swinger who roams the world enjoying his fetishes, sponsored by a major airline. Momus saw him as a cross between Iggy Pop, who sang of looking for “some weird sin, just to relax with” and the Japanese photographer Nobuyoshi Araki, known for his erotic work focusing on bondage, and women in states of submission. In Momus’ “Chinese” press release the Party writer identifies the Axis link between the German Shaftenberg and his Japanese collaborators, working together against the British Repressers of Sexuality.

The song kicks in with bass, electric piano, tinkling piano and a scratchy vinyl soundtrack: it’s a porn soundtrack from a 70s German film. Momus relates the tale, talking, close to the microphone, his seductive tones tinged with humour: in the first line we learn that the Professor is intelligent, learned, a psychopath and non-binary:

“He’s a polyglot, a psychopath, an androgyne

He likes to handcuff Japanese girls hanging upside down

He is rampant like the stallion

He wears the gold medallion

Of the Royal Order Of Reprobates Of Lichtenstein”

Some wah-wah guitar sounds and a high, sustained synth note join in. The second verse drives home the Professor’s sexual proclivities further and namechecks Araki. The song perhaps deliberately flourishes a stereotype of Japanese depravity, the legendary purchasing of schoolgirl underwear: this is probably an exaggeration, like the rest of the description of Shaftenberg.

Can you get good enough food for a gastronome in a love hotel? They are hotels designed to be hired by the hour or overnight only for purposes of, well, love. Or fucking. They may have a Chef, I suppose.

“He’s a bondage fan, a gastronome, a sensualist

Unparalleled for sinister lasciviousness

In a love hotel at half past four

He’ll purchase schoolgirl underwear

Meet Noboyushi Araki for dinner there”

Towards the end of the verse a female backing vocal or sample is added. For the chorus, the drums and percussion pick up, and play with more syncopation, inviting us to disco with the Prof. A female voice provides a backing vocal. Following the chorus, a vocoder appears and we lead with a funky rhythm and melody into the next verse.

“Professor Shaftenberg

Professor Shaftenberg

He is sponsored by Lufthansa

To screw the pants off Japanese girls”

Momus almost raps this section, the vocoder drops out but the female backing vocal is there again. “Pample mouse” is what the Momus lyrics page says, clearly he means grapefruit (pamplemousse). A frond is a large, divided leaf, as in fern plants, considered magical in Eastern European fairy tales. “The Song of Innocence and Experience” is a reference to William Blake’s two volumes of poetry published in the late 18th Century,

“The professor isn’t home right now, so this is the real me

I want to grind bones with a naked baby cow

I want to squash the squid and jump the junk

I want to peel the pample mouse pink to the pulp

Part the fronds and enter this , my magical place

Let us sing the song of innocence and experience”

The song switches back to the first verse style now, with the wah-wah guitar and female vocalist remaining. This verse steps up the sexual perversion again, with bestiality on the table. Also, Lotus flowers are in fact hydrophobic, water will roll off their leaves. “Snake Oil” is usually a reference to a bogus medical “cure” that in fact does nothing. Many particularly Eastern cultures use snake, tiger and other animal parts for cures or potions related to male sexual prowess. None of them work.. I am told. This is an indication that his claims of sexual potency may be somewhat exaggerated.

“He’s a zoophile, a hydrophobe, a lotus flower

He carries patent leather snake oil for his penis power

When it’s time to fuck their socks off

He boards his flight at Tempelhof

Countdown to Tokyo and zero hour”

“Professor Shaftenberg

Professor Shaftenberg

He is sponsored by Lufthansa

To screw the pants off Japanese girls”

The music changes now to include DJ scratching and more frenetic beats, which stop and start. Momus raps again for the next section, which describes the Professor’s lovemaking in more detail than we would ever ask for.

“You are culpable but highly fuckable

I’ll bring you home by midnight, death by chocolate, the horn by stealth of moonlight

I’ll stab you to the hilt

Satin you and jasmine you and, finally, critically

Drink the ectoplasmic jet

Grip and grab three hot bags of girly goddess head”

We switch back to the standard chorus, then back to another rap.

“Professor Shaftenberg

Professor Shaftenberg

He is sponsored by Lufthansa

To screw the pants off Japanese girls”

This rap is wordy, frenetic, frantic and feverish. Again we have the idea of duality: Momus is the “Reverend Hyde”, who is perhaps the voice that pipes up, high pitched, to complete the line “stunning from start to finish in performance and execution”. The next three lines attack religion, aim to shock, to pollute religion with sex just as religion aims to pollute and disturb our enjoyment of fetishes. He declares his desire to know the unknown, a desire so profound we get an echo effect on his voice to emphasise the depth of it, and equally, the desire to go to places he wants to go but has never been. This nearly spiritual evangelism is slightly undercut by the humour of the next line, to “get my rocks off before my cock pops off”.

“The Professor isn’t in right now but I’m his bastard cousin

The funky little pervert Reverend Hyde,

One superbad dude, come to my pad , let’s collude and let’s collide

Clasping and gasping, climax in unison, spermatozoon, clapping, coming

Consummate, original, stunning from start to finish in performance and execution

Invoke the deities, shock the pants off several

Choke on sacred bread and pollute the holy wafer

Inject a cloud of jism in the middle of the holy water

In clouds of unknowing I want to know

In places I have never been I want to go

I want to get my rocks off till my cock pops off”

The final chorus brings us to reality, the Professor is really pleasing only himself, and the declarations of sexual prowess, of being “stunning from start to finish” are probably just lies, in fact:

“Professor Shaftenberg

Professor Shaftenberg

He is sponsored by Lufthansa

To bore the pants off Japanese girls”.

The song stops here, with the vocals echoing the word “girls”, before the percussion skitters back in to give us a funky closing section, echoing away in the end like the apologies of Professor Shaftenberg as he rolls off another dissatisfied ingenue.

This is a funky little number, with a shopping list of depravities that is highly amusing, and the best thing about it is that there are, no doubt, numerous academics who live this kind of life, or think they do.

Shoesize of the Angel

An inverse version of “The Hairstyle of the Devil”. The original was about a man fascinated with his love rival, this song is instead about disinterest in someone who is not your rival at all. It is a musical, conceptual and lyrical reversal of the first song, not a sequel as such. It shares the mundane realism of the situation with the parodies Momus wrote to end Slender Sherbet, and in his notes Momus suggests that it is the lack of meaning in the events of the song and the lack of coincidental happenings which make the song something like real life, and real life more interesting than fiction. Terry Pratchett uses this as a trope in his Discworld series of fantasy novels, characters seem to almost be aware they are in a story, and seem to know, fundamentally, that “million to one” chances will always come off, that villains and good characters will always behave in set ways, to the extent that it bores them. Real life is much more interesting than fiction, because it is much less interesting. On the other hand, as Charles Dance’s evil drug baron Benedict says with delight in 1993 movie The Last Action Hero, as he crosses from a popcorn action flick into real life, “here, the bad guys can win”.

The song opens with Momus singing “Shoesize of the Angel” against a dance beat, fading in with a flanged effect which is played with and ends with the beat dropping out and Momus saying “shit…” A bass synthwave plays – and it may be a Moog being played in this song, a menacing tone against what is a fairly inconsequential set of events to play out. The song kicks in again with a synthesizer lead line which I can only guess is a musical inversion of the intro to the original song, there’s a bassline too which is disco driven, and as the verse begins a choppy piano, reminiscent of that on the original or in the late 80s/early 90s accompanies it. There is a sound before the first line, and under each one after that, which is as if the first word or breath of the song has been reversed, so it fades in. It’s another unsettling effect, deliberately at odds with the mundanity of the situation.

“I liked him from the moment we didn’t quite meet

Ignoring him by accident on Threadneedle Street

He was buying you a flower

He was speaking on the phone

He couldn’t wait to get home”

The piano comes in again between the verses. A choral keyboard effect (from the original?) also plays over the second verse. The lyrics are an inversion of the situation in “Hairstyle“: here the love rival is “violently calm” because he doesn’t know about the rival who doesn’t exist, rather than obsessed with one who does.

“His eyes remained blind to the undescribed friend

At your house he remained violently calm

At my house, where you never came, you spoke about him all the time

You were a very faithful woman”

The original has “shut up, don’t answer back”, here, and the fear that the love rival is better in bed, in this chorus it is the inverse. Each line is a mirror of the original’s lyric or intent in some way. These characters are cold blooded, repressed, English in fact. The chorus itself has a staccato synth line which mirrors the original. I need different words for mirror and original.

“Speak up, answer me

What do you say?

I know he doesn’t please you in a sexual way

I know he’s cold-blooded, I know he’s far away

But never reveal the shoesize of the angel

I said to my friend with indescribable lack of charm”

The second verse has the angel’s shoes being the evidence by which the interloper is found, rather than the devil’s hair in the original. Momus is simply sat on a chair wearing the shoes, stalking in the most obvious way.

“In the corner of the mirror he glimpsed the angel Michael’s shoes

I was crouching wearing them, sitting on a chair, right there in full view

Obvious to both of you, terrifying, ridiculous

Amidst no suspicious hairs”

Once caught and unable to vanish – “the sofa hid behind me” is a very good line to describe this kind of situation – Momus leaves by bus and is never contacted by the lady in question again, because why would she?

“The sofa hid behind me while he failed to disappear

So I caught a bus in daylight, and your conscience was clear

You couldn’t get enough of his disappearing love

And so you never telephoned me”

The Devil had his woman dressed up in black, so the Angel prefers to undress in white, cream and grey in the next verse. The lack of sexual prowess of the Angel, compared to the Devil is again mentioned:

“Speak up, answer me

What do you say?

I know he likes undressing you in white, cream and grey

I know he’s got no money, I know he makes you cry

But never reveal the shoesize of the angel

I said to my friend with indescribable lack of charm”

The opening section is repeated, with the flanging vocals and the lead synth line followed by the next verse. For the interloper here, Momus, the pervert, the Devil, the defeat is caused by what can overcome any sexual or other shortcomings, or repressions, what she sees in him instead is “irreversible love”. He goes on to attract no new partners, because he is “in full view of their boyfriends” – obsessed with infidelity, but finding it nowhere.

“The things you’d never spoken of seemed to turn him off

I worked out what you saw in him

Irreversible love

In full view of their boyfriends, I attracted no new partners

And you saw nothing great in me”

We return to the verse, again he demands answers. There’s an odd accent to the way he voices “What do you say?”, not sure what it is. Again he attacks the boyfriend’s sexual prowess “he leaves you dry”. But in the end, he speaks with “indescribable lack of charm” and is doomed to failure.

“Speak up, answer me

What do you say?

I know he likes undressing you in white, cream and grey

I know he’s got no money, I know he leaves you dry

But never reveal the shoesize of the angel

I said to my friend with indescribable lack of charm”

There is a key change now and a keyboard comes in playing a similar riff to that used at the end of “Hairstyle“. Whereas that song quoted the Rolling Stones “Sympathy for the Devil“: “Pleased to meet you, hope you’ve guessed my name”, here it is “with indifference I fail to meet you, You will not be learning my name”. In the background Momus chants “Ha Ha Beelzebub, stick him in the bottom with a Vaseline tub”. Instead of the menace of the dark Lord, we have an irrelevant and charmless stalker who presumably walks rather awkwardly.

The song ends, ironically, with a flourish of horns, and one last rendition of “ha ha beelezebub…”

For all that this song is six and a half minutes long, and a mirroring of Momus’ most famous track to date, it flashes by almost unnoticed, both musically and lyrically. This is the intention of course, the narrative is slight and meaningless for the reasons I gave in my introduction to it. Linger and listen though, and there is some great humour and invention in the lyric and the musical backing.

The Age of Information

Douglas Rushkoff, the media theorist and writer associated with the early cyberpunk and internet movements, believed that the solution to the problem of privacy on the internet, already a major concern in 1997, was that everyone should just become morally good. Since all information will be known to everyone, the best thing is not to do anything you don’t want to be public. This would not necessarily mean becoming overly respectable or anodyne however, as this new transparency would lead to new standards of acceptable behaviour. Momus posits as a then current example the fact that Nixon was impeached for Watergate, but the scandals caused by Bill Clinton’s infidelity and novel use of dresses only made him, if anything, more popular.

This song condenses what Momus thinks about the topic of privacy on the internet and the new norms of behaviour. He is positive about the idea of transparency of public knowledge, believing that since all knowledge will be available, Governments will find it harder to conceal facts, and need to change their interpretation instead, i.e. spin them. He wrote this before the General Election of 1997, when the Labour party came into power with Tony Blair as the face of New Labour, and proved him right by immediately spinning the country into illegal conflicts. The Labour Party promised much, but along with the rest of Britain, Momus would become disillusioned. Their slogan and theme song of the time – “Things Can Only Get Better” by D:Ream (with Professor Brian Cox on keyboards, an absurd fact) was just one of the complex and cubist facts they slung about. Labour collaborated with many heroes of BritPop, and invited many pop stars of the time to Downing Street. Jarvis Cocker recounts the story of such an invitation on the song “Cocaine Socialism“, with some horror I think. Such an invitation meant the death of any credibility, the phenomenon even had a name: The Curse of Thrashing Doves: a band whose song “Beautiful Imbalance” appeared on BBC1’s morning kid’s show Saturday Superstore and was glowingly endorsed by Margaret Thatcher, who “loved it”, and thus doomed them to obscurity. The video for the song includes a band member holding up a model cruise missile. I digress.

The problem with Momus’ view of information at the time is that the flow of data is two ways. The information held by Google, Amazon, Microsoft and Facebook – and at the time, I don’t think anyone could have dreamed of how much data that would be – may as well be held by the Government, because they certainly have access to it, regardless of what any institution involved says. Privacy and Encryption are huge topics of debate, and the right to a private conversation remains a battlefield. Having said that, much of what Momus says in this song is well reasoned, cleverly predicts developments and is correct. It is interesting how we have fallen into these new conventions without much argument.

The song begins with a flat 4/4 bass drum beat (with eigth note beats in each third bar). The main melody is played on a keyboard sound that is like, I guess a kazoo, and runs in tones up the scale of F. Momus intones “This is a public service announcement” to a cymbal crash, and in 1997, you needed to hear this. The verse is accompanied by general “digital data” noises playing in the background, representing the flow of data. An electric piano sound plays chords as a rhythmic accompaniment.

“Ladies and gentlemen, we are now entering

The age of information

It’s perfectly safe

If we all take a few basic precautions

May I make some observations?”

We switch key now (Dm?) and learn a home truth.

A double tracked, lower vocal joins in.

“Axiom 1 for the world we’ve begun:

Your reputation used to depend on

What you concealed

Now it depends on what you reveal”.

A key change again, which could be C major as it seems to be another home truth.

By “mandarins” he is referring to the Whitehall officials we see in comedies such as “Yes Minister”, whose job was to conceal truth, and who now have to “reimagine” the truth instead. A synth joins in, playing longer chords in emotional counterpoint.

“The age of secretive mandarins who creep on heels of tact

Is dead: we are all players now in the great game of fact instead

So since you can’t keep your cards to your chest

I’d suggest you think a few moves ahead

As one does when playing a game of chess”

For the next verse a woodwind sound is added, which plays another emotive counterpoint, almost a pastoral sound. Subtly, more percussion is added as each axiom comes in. Netscape was a browser which was once dominant, but died out when Internet Explorer came in.

Cookies are small files stored on your computer by websites in order to save information about you, your machine, your session or.. whatever. At the time the “magic” cookies would be used to store mainly identifying data about your website visit (session).

“Axiom 2 to make the world new:

Paranoia’s simply a word for seeing things as they are

Act as you wish to be seen to act

Or leave for some other star

Somebody is prying through your files, probably

Somebody’s hand is in your tin of Netscape magic cookies

But relax:

If you’re an interesting person

Morally good in your acts

You have nothing to fear from facts”

Here Momus talks about facts: a louder synth sound again plays a line emoting against this.

This verse describes acutely the difference between the world before the internet and now. Privacy now means something very different, we have no expectation of it anywhere.

“Everyone should prepare to be known” was very much the situation, the last days of being able to “not exist” outside real world meetings was upon us.

“Axiom 3 for transparency:

In the age of information the only way to hide facts

Is with interpretations

There is no way to stop the free exchange

Of idle speculations

In the days before communication

Privacy meant staying at home

Sitting in the dark with the curtains shut

Unsure whether to answer the phone

But these are different times, now the bottom line

Is that everyone should prepare to be known

Most of your friends will still like you fine”

So the bottom line is, is there anything you wouldn’t want your friends to know? Any particularly exuberant self-pleasuring methods? Any connections, any past regrets or mistakes you have made? Any aspect of your footprint you will need to manage, re-frame and re-position in their minds eyes?

The following section changes to a faster rhythm from the piano chords, and accurately describes what used to happen with communication when it was merely two people at a time:

“X said to Y what A said to B

B wrote an E mail and sent it to me

I showed C and C wrote to A:

Flaming world war three”

That Momus sees this world as inevitable is marked by the martial, imperative, declarative nature of the next two lines, bolstered by a sharp synth line.

It now seems quaint to talk in terms solely of email, of course, “CC” meaning Carbon Copy.

“Cut, paste, forward, copy

CC, go with the flow”

The next two lines are softer, and accompanied by a swell of synth chords, which then falls down to the decision, “simply to go”. But go where, when the entire world is infected? And if our self-knowledge proves unloveable, then what can we do?

“Our ambition should be to love what we finally know

Or, if it proves unloveable, simply to go”

We return to the verse after a reprise of the introduction.

This verse discusses loyalty, and the fact that we will in this new world change our loyalty depending on “who we are speaking to”. Again, this is a view very much predicated on Web 1.0, which was mainly static, and relied on old fashioned duplex communication. In fact we live in the dying age of Web 2.0, where communication is multi-faceted and constant, and messages are broadcast rather than “sent”. In other words, it isn’t about “who I’m speaking to and who they speak to in turn” any more, because you are probably communicating with them all at once. This is the logical next step, where facts are transparent to all, equally and concurrently.

I do love the idea though, that Momus is telling the person he is addressing about this world view, about being “disloyal” to them in this new world. So are we now for or against information? With Edward Snowden, Julian Assange etc. and their information leaks, are we really on the side of those in charge of the information? Our loyalties really are complex, and cubist. We say all that we say about the dangers of information but we still use Facebook and Amazon, and a part of us thinks that “if you have nothing to hide, you have nothing to fear”, and believes that simple lie.

“Axiom 4 for this world I adore:

Our loyalties should shift in view according to what we know

And who we are speaking to

Once I was loyal to you, and prepared to be against information

Now I am loyal to information, maybe I’m disloyal to you

My loyalty becomes more complex and cubist

With every new fact I learn

It depends who I’m speaking to

And who they speak to in turn”

In this final verse Momus seems to go over the top, demanding that workers always supply the information required regardless of the interests of those requesting it.

Which sounds dystopian, fascistic, and impossible to us, and yet, we have given all our information away freely to companies who trade it all on to whoever pays best. We have given the Government access to this same information and we have done so without any boots having to crush any human faces. We have given away every aspect of our freedom, every last and minute aspect of our day-to-day lives for no reason at all, except convenience.

“Chinese Whispers” is the game known as “Telephone” in the USA. I would leave as a discussion point whether, in fact, digital signals really improve as they spread. I would argue that “noise” in this case, is not just caused by the factors of transmission as it would be in an analogue example, but also by the addition of interpretation, bias and opinion from every single person involved in the chain. The message may become clearer in the sense of High Definition but the frame, the meaning, degrades. Just look at the nonsense spouted in the last General Election in the UK. I have no doubt that clips of Jeremy Corbyn and Keir Starmer re-used by the Conservative Party were just as good quality as the original in terms of pixels and technical dimensions, but the “Meaning” of them was distorted, warped, lied about and re-written by every right wing supporter who commented, shared and re-tweeted.

“Axiom 5 for information workers who wish to stay alive:

Supply, never withhold, the information requested

With total disregard for interests personal and vested

Chinese whispers was an analogue game

Where the signal degraded from brain to brain

Digital whispers is the same in reverse

The word we spread gets better, not worse”

We return to the mid-section, and the song concludes after this with instruments dropping out until a single synth line, slightly at odds with the melody, remains, sinisterly hanging there, belying the optimism the rest of the song seems to have.

“X said to Y what A said to B

B wrote an E mail and sent it to me

I showed C and C wrote to A:

Flaming world war three

Cut, paste, forward, copy

CC, go with the flow

Our ambition should be to love what we finally know

Or, if it proves unloveable, simply to go”.

In fact, I seem to be less optimistic now than Momus was then in this song. I love the technology, but do not generally love the people using it. Discussions on Twitter for example can be very depressing, and yet, especially in the lockdown we face now, this technology is enabling a sense of community to remain, empowering those who have access to it. And that is the key: those who have access to it. Which is not everyone. As a lecturer I am aware of a divide between those who have access to devices, access to broadband, access to knowledge, and those who do not. It is not a divide merely between young and old, north or south or cultural: it is a social divide caused by inequity of income and opportunity, and our major challenge to overcome if we are to create a truly functioning society in the age of information.

The Sensation of Orgasm

In 1993 Momus was asked to write a song for a Finnish documentary about Jean Baudrillard: the French sociologist. Baudrillard believed the end of history had come, a similar view to Francis Fukuyama, however whereas Fukuyama believed a pinnacle of democratic process had been reached, Baudrillard believed that further progress was just impossible, and the utopias that both the left and the right political wings dreamed of were illusions. He also wrote about hyperreality: the idea that reality and simulations of reality were (or would become) indistinguishable. Baudrillard decided not to take part in the documentary and instead we got the Man of Letters documentary about Momus, and this song. The section of Man of Letters featuring the song is here: Momus is a member of The Orgasm Party and in his party political broadcast tries to persuade you to turn out for him. How could you resist? Subsequently the song was recorded by Laila France on the album Orgonon. This recording by Momus could have been a 20 Vodka Jellies oddity but has been kept for Ping Pong. It is very simply about the power of Orgasms: the energy released by them, which enables them and that is put into obtaining them. It relates to the experiments of Wilhelm Reich in capturing the universal force “Orgone” through experiments with “orgone accumulators” at his home refuge “Orgonon”. The song asks us to think about how all the achievements of mankind, all the heads of state, all the scientists, artists and achievers, all exist only because someone wanted an orgasm, and all the machinery of the world that keeps society running does so chiefly because we want orgasms.

The song begins with a funky beat, bass riff and a keyboard, playing short chords as an acoustic guitar as the verse builds the necessary tension, Momus’ voice quiet as he relays the party message to a serious sounding tune:

“For the sensation of orgasm

Civilisations must rise and fall

For the sensations of orgasm

We build the society of spectacle”

A pretty and more optimistic sounding chorus follows, musically very similar to something like “Amongst Women Only“, slow, seductive, slightly squelchy. Our Human Rights and our lawyers give us freedom, with which we can practice the release of energy.

“Oh these are beautiful powers

And these are beautiful human rights

And we have beautiful lawyers

Freedom is keeping us up all night”

It is interesting that in this second verse, the new order “allow the transgressions…”, a million miles from the world of “Song in Contravention“, where many such acts carried illegality. A circling keyboard line plays above.

“For the sensation of orgasm

Cultures accumulate energy

And for the pleasure of citizens

Allow the transgressions of chemistry”

This chorus seems to attack the tendency of “citizens” to elect by “desire” and to elect “pretty things”: to vote for the most pleasing telegenically. Some “electronic”, “data” type sound effects play in the background.

“Oh these are beautiful powers

And we are dutiful citizens

And we elect by desire

Yes we elect only pretty things”

Again the idea of an election is compared to sexual appeal: the power and transfer of power given by the voters is comparable to the release of orgone. For the last of these four lines, there’s a multi-tracked low backing voice from Momus.

“Famous performers who win applause

From the anonymous everywhere

Show us that life is just metaphors

Sex is the air and the atmosphere”

He now critiques the performance of lovers, who, like all lovers, feel that they invented sex:

“Oh you’re such beautiful movers

And your performance was fabulous

You think because you are lovers

You were the ones who invented this”

A short instrumental break follows featuring some of the sexual noises you would expect, similar to “Amongst Women Only“.

As this song is – if anything – about communication between individuals and between levels of society, the comparison is now made to a Tower of Babel, an attempt to breach heaven rendered futile by the inability to communicate.

“Each day I build a great tower

Where they speak thousands of languages

Oh these are beautiful flowers

And these are fabulous sandwiches”

Sex is intercourse, as is discourse and communication, sexual congress is compared to political congress, and the ability to voice your opinions is compared to the right to scream in pleasure, or pain, whatever is your thing.

“All the sensations of orgasm

Here in the congress of intercourse

These are the rights of the citizen

You may shout till your voice is hoarse”

The chorus now has double tracked vocals all the way through. The cynicism of the “political ideal” we have been sold is laid bare now. Yes we have beautiful colours, and lovely arithmetic (which allows the building of the towers, the breeding of the flowers, and the mass production of sandwiches), but the political system we have is indeed what makes us sick. Mentally, physically, psychically and morally. As is so often the case with Momus, the beauty of the melody and the instrumentation disguises the coldness and bile released in the words.

“Oh these are beautiful colours

And this is lovely arithmetic

This system’s been designed for us

It’s such a pity it makes us sick”

The sexual noises continue as the song, unusually, fades out during the verse. This denies us an ending or release, appropriately enough. Just as the political and social system we have metaphorically promises all sorts of orgasms it never provides. The healthcare orgasm, the fair benefits system orgasm, the education jizz fest..

It’s cleverly delivered, notice how Momus sings very slightly off note for “love” in “love police” to lay emphasis on how dystopian this kindly-sounding-system would actually be.

“All the sensations of orgasm

Empower me afresh with a rush release

All the sensations of orgasm

Patrolling the borders with love police”

This is a very pretty song, disguising a disgust at politics and leading us on a science-fictional trip to some Brave New World that would definitely be hell. I feel it may have slid in better to a slot on 20 Vodka Jellies, but it’s still welcome here as a slight aside, before diving into the world of Shibuya-Kei.

Anthem of Shibuya

Following the Second World War, Japanese culture was shattered. However, the Jewel Voice Broadcast was heard only as an echo to the children of the 60s and 70s, who by the 1980s began to create a new cultural movement of their own, inclusive of traditional Japanese music and theatre, but incorporating outsider influences. There were those who sought to maintain cultural isolation, to stand fast, but the young magpied jazz, bossa nova, ye-ye, lounge music and English and US pop and rock influences into their music. This was particularly true of young urban Japanese, whose genre of City Pop united all these disparate influences. Two bands in particular: Pizzicato 5 and Flipper’s Guitar were recording albums mixing loungecore elements with pastiches of 60s European pop. Initially their albums could be mistaken for pastiches, but by 1990 a distinctive genre was emerging which included new musical elements. This gained particular traction in the consumer district of West Tokyo called Shibuya, and the movement became known as Shibuya-Kei. Flipper’s Guitar included Keigo Oyamada, and a compliation album in 1990 called Fab Gear included Flipper’s Guitar and Momus, and solidified the sound of retro-futurism that characterises Shibuya-Kei. Also the Flipper’s Guitar album Camera Talk and song “Young, Alive, In Love” came out that year, definitive texts of the genre. Other artists became key players in Shibuya-Kei during the 90s including Kahimi Karie and Momus. It is fair to say that Keigo Oyamada’s album Fantasma in 1997 (recording as Cornelius by now) defined and idealised the genre to such an extent, popularising it worldwide, that it also killed the genre by negating the possibility of playing with the definition of it. It would equally be simplistic to say Shibuya-Kei/Japan equates to Britpop/UK, but may help to give a shorthand to understanding what the genre was. Momus describes the scene in Shibuya in the 90s as a product of Japanese teenage girls, who wear “lolita” space costumes, speak an arcane slang which “the business men who are queuing up to buy their underwear cannot understand”, buy pink gadgets and Cornelius records, and no doubt spend a huge amount of money. Shibuya also had great record shops, and large numbers of love hotels. Momus points out that the area has zero crime – which seems unlikely but could have been true at the time. It is also interesting that he feels he needs to defend Shibuya in this way. I would never have thought that more-respectable-than-you-think love hotels and rich teenage girls added up to a huge crime spree, but thank you for confirming that.

It sounds great, to be fair. This song is a celebration of a place, time and scene that Momus clearly loved and was an essential part of. For this he has written a national anthem: this is the time, and this is the record of the time.